SELECTED PROJECTS

Osservazioni improprie sul lapis tiburtinus, 2024.

at Palazzo Orsini di Licenza. RM. Italy.

at Palazzo Orsini di Licenza. RM. Italy.

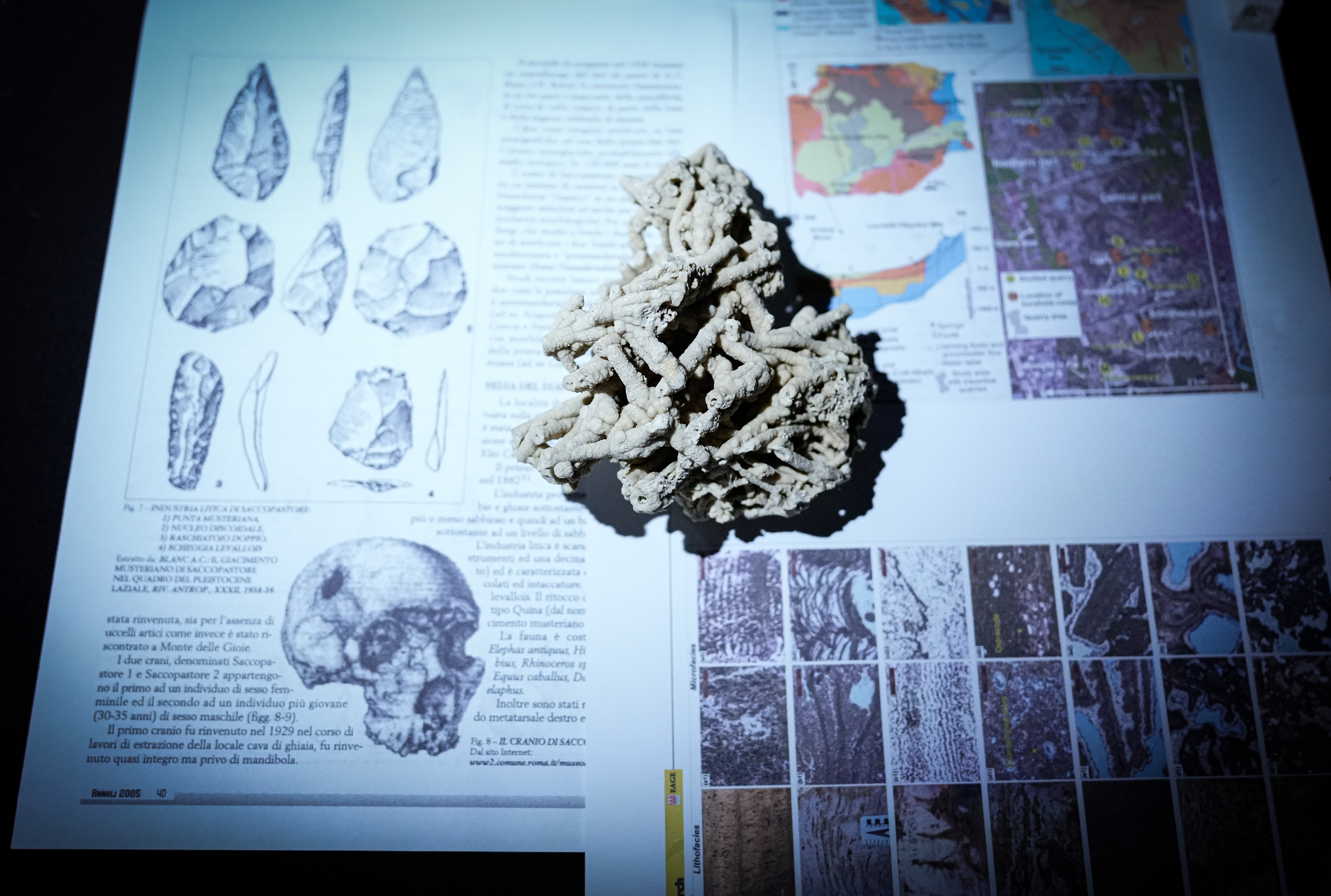

Erosion Mechanics is a project that investigates the relationship between contemporary art and the lithic industry through a series of procedural and visual exercises approached from an interdisciplinary artistic perspective. These exercises will be developed as a fieldwork-based dialogue between the sculptural and documentary heritage of the collection at the Chilean National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA) and the travertine extraction zone of “delle Acque Albule” in Italy. All of this is framed within a theoretical context that brings together media theory, new materialism, and posthumanism.

Curatorial text

Stone and Time

Claudio Guerrero Urquiza

We use clocks, agendas, and calendars; we rest on certain days and work on others; we generally value punctuality; we celebrate anniversaries and elect representatives and rulers for specific terms. We understand and plan our lives, on both small and large scales, according to some idea of time. But things become more confusing when we try to describe time, explain what it is, and how we perceive it.

Perhaps geology can offer us some clues to perceive time. Avicenna, a Persian philosopher and scientist who lived a millennium ago, is said to have been the first to formulate what we now call the principle of the superposition of strata. This means that layers of sediment accumulate in the soil over time, with the oldest at the bottom and the newest on top. In this sense, soils and rocks may be the most direct perception of the passage of time, condensed in a matter we can experience with our senses.

Lapis tiburtinus or Roman travertine is a sedimentary rock—wrongly referred to in the Americas as “travertine marble,” although it is not exactly marble. It forms through the accumulation of sediments under specific conditions found in the landscape of Guidonia and Tivoli (RM), such as the distinctive features of the Aniene River basin and especially the presence of the Acque Albule. Compaction and high temperatures turned these sediments into rock, but a careful observation reveals that their formation was a process of extremely long duration; chronostratigraphic studies date it to around 100,000 years.

We would know far less about travertine if the ancient inhabitants of this region had not discovered its constructive and ornamental properties. In particular, we might not be discussing it today if the Romans had not begun its industrial extraction around two thousand years ago. Some of their most admired and well-known monuments were built with this stone, so its extraction grew alongside the expansion of the empire and the later hegemony of classical architecture and sculpture. These were closely associated with marble and experienced renewed development during the Renaissance (15th and 16th centuries) and Neoclassicism (18th and 19th centuries), when the aesthetic even crossed the Atlantic to settle in the Americas, further increasing demand for these stones.

Two millennia of industrial extraction have transformed the Guidonia landscape and stand as early evidence of human activity shaping the world as a geological agent—something that may seem obvious today if we look at the landscapes left by extractivism: from open-pit mines and massive tailings fields to forests razed for monoculture plantations, and even climate change driven by greenhouse gases.

Along with the expansion of the classical artistic paradigm, pieces of stone (travertine, Carrara marble) circulated as raw material for sculptors and art academies across the Western world. Sculptures created by Italian artists also adorned buildings and public squares (such as the Plaza de Armas in Santiago, Chile). Simultaneously, sculptors, artisans, and marble merchants traveled from Italy to the Americas, while the journey to Rome became nearly a rite of passage for American artists.

Chilean artist Jose Ulloa Acosta’s proposal at the Palazzo Orsini in Licenza may be seen as a new version of this story that links art, stone, Italy, and the Americas. This time, however, stone is not simply a raw material or a means to another end—it is the central focus of an exploration where art and science engage in dialogue. The visual exercises on display result from his research conducted during a residency at L'Aquila Reale Centro d'Arte e Natura in Civitella di Licenza. Over five months, he carried out fieldwork exploring the travertine industry, emphasizing the stone’s extractive, geological, and heritage dimensions.

The exhibition connects the archaeological vestiges from the Palazzo Orsini Museum’s collection with the landscapes of the lapis tiburtinus quarries in the Acque Albule area. It integrates multiple languages: scientific and bibliographic documentation, material samples, 3D digital prototyping, 3D animation, and video records of territorial interventions. Through this multidisciplinary assemblage, it invites us to reflect on matter as a vibrant agent (Jane Bennett) and proposes art as a critical tool for rethinking the impact of the present and imagining future projections of the relationship between human beings and material and natural resources.